Rembrandt’s Good Samaritan, Then and Now

by Adele Ne Jame

Beggar Seated on a Bank. Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn). 1630. Etching. 4 3/4 x 2 15/16 in. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

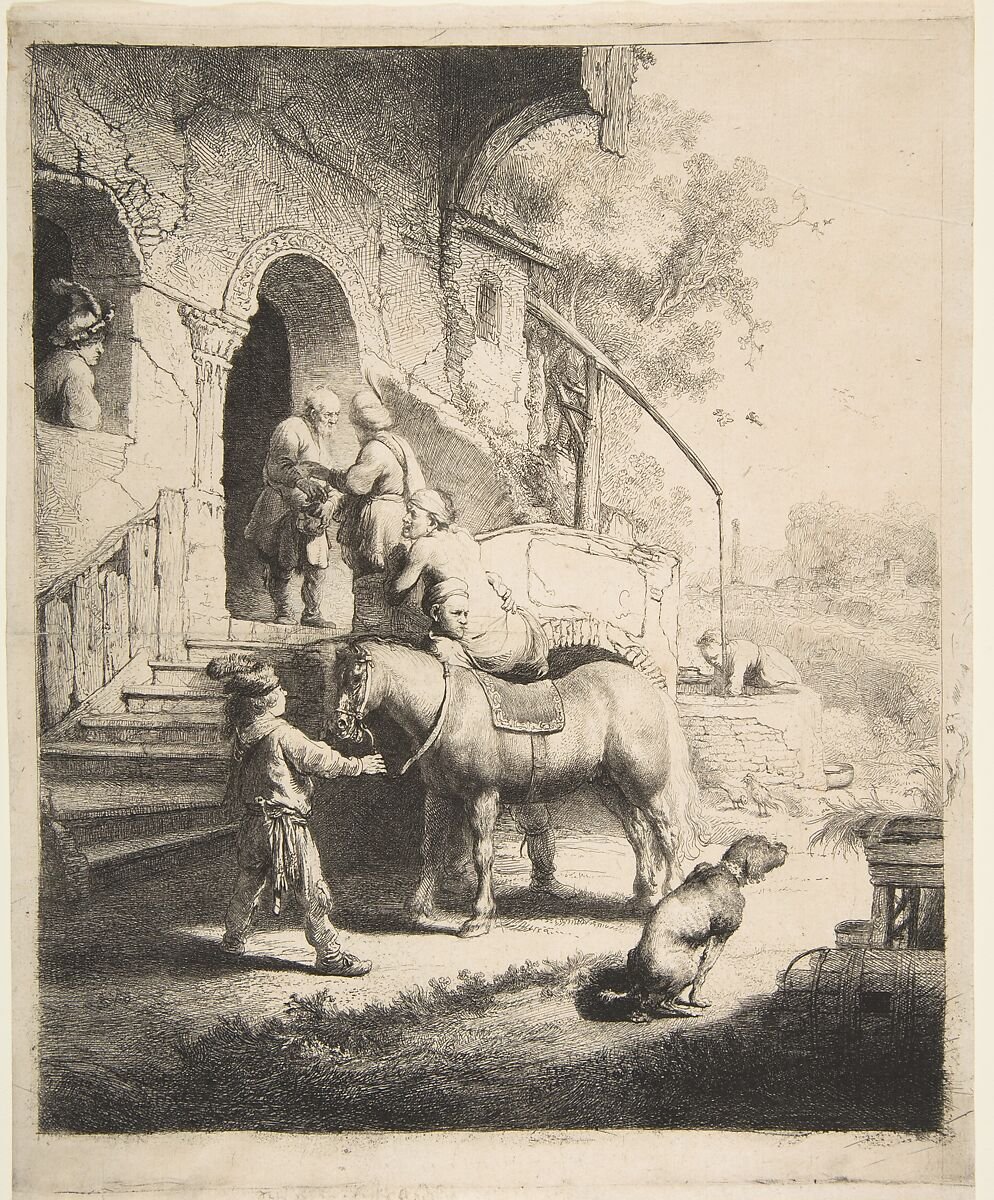

The Good Samaritan. Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn). 1633. Etching, engraving and drypoint. 10 9/16 × 8 7/16 in. Courtesy of The Met.

Of all his self-portraits, perhaps

we most love Beggar Seated on a Bank,

hunched in rags, scruffy hair,

broad nose, the mad glint in the eye.

Some say he is groaning in misery,

a palm extended out to us, who knows

whether for alms or recognition.

Though the artist thought himself ugly—

and preferred it to the beautiful,

his love of nature gave us beauty

despite his dead birds

or dogs doing what dogs do

as in the Good Samaritan.

There we see all—

a man who stops to help a stranger,

a ransacked traveler, beaten

by robbers and left for dead.

Others, so the story goes, including

a priest, saw but turned a blind eye

hurrying off to the other side of the street—

so that we catch our breath in shame.

But the Samaritan rushes to

douse his open wounds

then sets him on his own animal

and leads them to an inn.

When the Samaritan pays the innkeeper

and promises to return,

the artist melds the earthly (the dog

in the foreground) and the spiritual.

Some say the artist saw the parables

as an account of moments in his own life,

this master who harnessed the forces of

light and dark, who plunged

so deeply into the mysterious

that Van Gogh thought him

a magician. This man who suffered

the loss of three children and his Saskia,

who wiped his dirty brushes on his clothes

not caring a whit what others might think

was happy in the company of

workers and street people.

All his life a spendthrift,

finally, he died poor and

was buried in an unmarked grave—

Still we have the gift of his heart-work,

like deep music that moves

through rivers

opening and opening –-

and the marvel of this etching

revealing the faces of all those outside

the inn, but not so the Samaritan.

His back is turned to us thus becoming

the embodiment of the injunction:

Do not let your left hand know

what your right hand is doing.

Though he remains anonymous,

his radiance burns white hot.

Adele Ne Jame is Lebanese American and has lived in Hawai'i most of her life. She has published three books of poems and won many awards including a National Endowment for the Arts in Poetry, a Pablo Neruda poetry prize and an Eliot Cades Award for Literature. She has taught creative writing at the university level for decades also serving as the Poet-in-Residence at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and her poems as broadsides have been exhibited both at the Sharjah UAE International Biennial and at the Arab American National Museum.