An Enfleshed Spirit

Reflections on Cole Arthur Riley’s This Here Flesh: Spirituality, Liberation, and the Stories That Make Us

by Kolya Braun-Greiner, MDiv

224 pp., paperback, $18

January 2023

Convergent Books

ISBN: 9780593239797

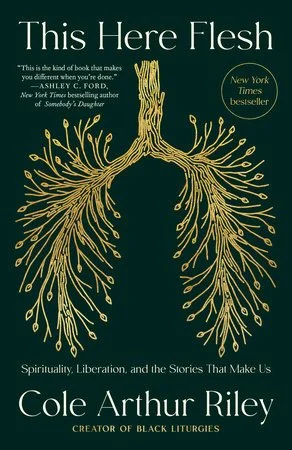

Sometimes we are so disembodied that we miss the obvious. Such was the case when I saw the inverted tree image in the shape of dendritic golden-leafed lungs on the cover of Cole Arthur Riley’s This Here Flesh – Spirituality, Liberation, and the Stories That Make Us.

I read this book as a member of a class at my church, where participatory sharing of our storied lives is a primary practice. I slowly acknowledged how relevant the cover’s image is to me and my body: I have a lung disease of unknown origin and uncertain future outcome. Riley’s writing hints at some similar chronic illness that plagues her with pain and fatigue. She calls me to join her to “inhale-exhale in stillness, liberated from the breath of my body.”

This Here Flesh invites the reader to discover their own embodied stories. Riley encourages us to “go deep and old,” like a tree, so that our stories can be discovered or recovered. What stories reside in your body?

Riley identifies herself as a storied contemplative, and “this is a book of contemplative storytelling,” with pages “wet with tears.” Her sort of contemplative is one who practices paying “sacred attention” to our lived experience, aware of and open to the Spirit’s leading and how it is showing up in this incarnate world. The pathway into this is a practice of beholding the divine in every present moment that we receive and give the breath of life. The wisdom of Thomas Merton’s revelation expresses the fruit of this kind of contemplative attention: “Nothing has ever been said about God that hasn’t already been said better by the wind in the pine trees.” A way to do this, Riley suggests, is “if you have forgotten how to marvel, try staring at something beautiful for five minutes and see where your mind goes.”

Each chapter is a portal into Riley’s experience as an African American woman whose history of trials, trauma and survival has shaped her story. Her chapter titles offer a litany of these portals, each of which is a doorway into another embodied practice, state of being, and perspective based upon her own story of personal struggles and family history: Dignity, Place, Wonder, Calling, Body, Belonging, Fear, Lament, Rage, Justice, Repair, Rest, Joy, Memory, and Liberation. Through each of these “our knowledge of the spiritual is deeply entwined with the sensory.”

We come to find our true selves when we discover and live out God’s intention for us, the one that breathed into life with our birth.

Entering the chapter/portal of Calling, Riley proclaims that discovering one’s true self is inseparable from discovering God. We come to find our true selves when we discover and live out God’s intention for us, the one that breathed into life with our birth. “My journey to the truth of God cannot be parsed from the journey to the truth of who I am.” She declares that this journey of “knowing the soul should be relentless”; however, it is not one of isolated egotistical purpose and focus; it has implications for the community: “…your calling into selfhood may enhance the sound of self in someone else.” Her invitation suggests that with intention, a community can be the source and sustenance for one’s true self to be revealed and affirmed. What are the truest things about you? Are there people in your life who could mirror that for you? Riley counsels the reader to “protect the truest things about you and it will become easier to hear the truth about everyplace else.”

Perhaps the most potent chapter/portal is Lament, a place of truths that are hard to hear. Given the plethora of reasons to lose hope these days – from systemic racism and violence to the desecration and diminishment of biotic life systems on Earth, her affirmation that “lament itself is a form of hope” and her refreshing definition of it as “an innate awareness that what is should not be” seem like a powerful “balm in Gilead.” One can easily be tempted to despair, but that is not lament, because that “sinister sadness” is devoid of hope. Especially for those who have experienced abuse or enslavement of bodies, hope and lament are inextricably connected and interdependent because “our hope can be only as deep as our lament.”

For Christians who espouse a gospel of “good feelings” or “positive thinking” or “escaping a someday hell,” she suggests that if they started paying attention to current hellish conditions, then more people might flock to their churches. Lament in that case is a collective act, “a kind of art that is for healing and not for consumption... [and] Black lament is something to behold [where] some churches know how to shake the numbness from your flesh.” This embodied lament is expressed by her father’s trapped agony over his loss as a young man of his buddy Mario, who sped down the street and crashed into another car, killing two elderly couple, both cars exploding. “We were just with him,” her father thought; “I should be dead.” The delayed expression of lament held within his body was finally released when he witnessed the Challenger space shuttle explosion on TV—he bowed his head and let out a scream.

Riley reminds us of the deeply rooted tradition of screaming a lament: Jeremiah 9:20 calls out, “Hear O women, teach your daughters a dirge, and to each to her daughter a lament.” Lament is intergenerational and it can be taught. The keening of the women expressing the pain of their exile voiced the lament of the community. It can echo today within stories of intergenerational grief. Walking a prayer labyrinth with Sister June, she too learns how “to cry with will and with purpose [and] to feel the tears on my face and not wipe them away.” She discovers that our “wails are worthy to be heard.”

What power could be unleashed with a massive intergenerational lament for the loss of innocent black bodies gunned down? Or for the loss of so many other living strands in the exquisite web of God’s creation?

What power could be unleashed with a massive intergenerational lament for the loss of innocent black bodies gunned down? Or for the loss of so many other living strands in the exquisite web of God’s creation?

In her chapter/portal of Belonging, Riley affirms that “we need other people to see our own faces—to bear witness to their beauty and truth.” She voices the desire we share that “we could behold the image of God in one another and believe it on one another’s behalf.” As a pathway into this experience, she returns to the symbol and sensory experience of hearing her favorite sound, the wind, and the feel of it on her skin, the very breath or Ruah of God “put in you and me [that] will stir and recognize herself for a moment.”

She confesses that during her twenties she saw herself as a loner, hidden, even while sharing an apartment with two other women that “looked like a commercial trying to meet a diversity quota: Black, white, and Taiwanese American.” Her habitual distance led the other two to believe that she hated them, a response which surprised her. While solitude was necessary to her soul, she came to realize the truth of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s wisdom: “… each individual is an indispensable link in a chain. Only when even the smallest link is securely interlocked is the chain unbreakable.”

This is a kind of mutuality of belonging, which is in her words “both a gift received and a gift given.” Our truly unique self is both revealed by and essential for the strength of the links in all our connections with other lives. “There is a comfort in being welcomed, but there is dignity in knowing that your arrival just shifted a group toward deeper wholeness.” What a lovely test for a healthy community – that our longing to be and be-longing can offer a gift of transformation for the wider world!

Our truly unique self is both revealed by and essential for the strength of the links in all our connections with other lives.

This call to transformation, however, is too often thwarted by “the need to protect ourselves” so that we are “prone to avoiding rest.” Thus the chapter/portal of Rest, of which so many of us are bereft. With great insight she names another kind of pandemic: widespread psycho-spiritual and physical exhaustion. Her father, “the hustler, never really learned how to rest” because he was working so hard trying to survive and support his two daughters. When he finally called his sister for help, she arrived, took care of the girls and told him to go to bed, so he “slept for forty days and forty nights.”

Here we see again how community is necessary for our well-being – in this case for rest. “In solidarity my father’s mother and siblings made his sacrifice, the sacrifice of the collective. They became harbors, allowing him to find a stability of heart-peace in a maddening world.”

In This Here Flesh, Riley’s practices open the reader to the wider world where God’s presence can be found in expansive and communal ways. They act as a corrective to privatized religion and individual salvation and move us to collective experiences of healing and interdependence with other humans and with the more-than-human world of this Earth. Riley offers wisdom in the tradition of the mystics who express that our embodied self, our true self, is rooted in community, and is an incarnate expression of Spirit or Source. Teilhard de Chardin reminds us: “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience, but spiritual beings having a human experience.” Our human experiences are indeed the roots of our spiritual tree, whose branches bear fruits of the Spirit — compassion, love, peace, and justice, the acts of “this here flesh.”

Kolya Braun-Greiner is a member of Seekers Church and former program coordinator with Interfaith Partners for the Chesapeake. She has created curricula and facilitated trainings for people of many faiths to explore connections of their tradition with care for the environment. She is currently working on a book about contemplating nature as a way to foster reverence and healing for Earth.