Never Yet an Emptiness

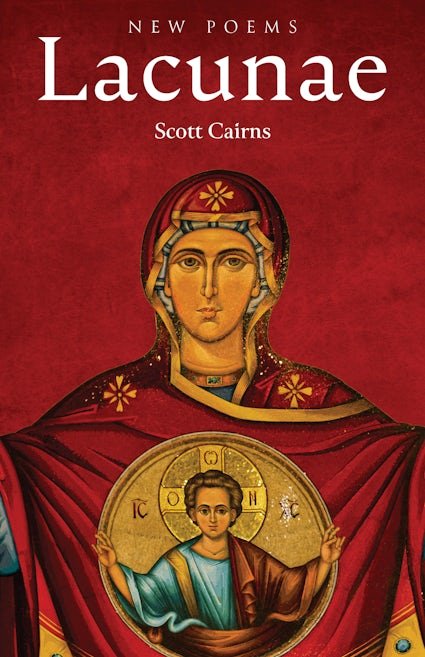

A Review of Lacunae by Scott Cairns

by Matthew J. Andrews

For Cairns, the mission of every slow pilgrim is not to rise above the world into some ethereal realm of the holy, but to learn to see the holy in and around us.

112 pp. paperback, $21

Nov. 7, 2023

Paraclete Press

ISBN: 9781640608818

One of the great ironies of being a writer who primarily deals with issues of faith and belief is that the center of these things, the God around which the whole enterprise spins, is often the hardest thing to write about. How do we, nearsighted and bereft of anything close to an appropriate vocabulary, describe what is, by definition, indescribable? To even think that it can be done is to fail from the start.

There are many things that I love about Scott Cairns, but chief among them is that he gets it. He writes, perhaps better than anyone today, about the magnificence of God, and he does so primarily by focusing on the folly of the task at hand. The resulting poetry is both uniquely insightful and delightfully self-deprecating. One only needs to peruse the titles of Cairns’s prior books (Idiot Psalms, Slow Pilgrim) to see the tone he’s consistently achieved in his career.

With Lacunae, Cairns’s newest full-length collection, there is certainly more of the same. In “Ain’t No Meta. Ain’t No Nevamind,” Cairns imagines humanity, in all its stupidity, staring up into the night sky: “we cannot comprehend / your comprehensive quiet, nor / the countless sparkling lights all / but laughing amid that bleak, broad / immensity above, beyond / which we cannot imagine much.” The theme comes up again, often in the form of epistles from Isaak (Cairns’s poetic alter ego) to unnamed churches. One such poem is “Η Θεολογία: God Talk,” and in it he writes, plainly, “Get a grip. Know this: One God, / and that God is wholly incomprehensible.” He follows this up with, “Know this: You only know what you can know, / which isn’t near enough.”

Yet if there is an overarching theme for this collection, it is one of grace. Many of these poems dwell in the divine mystery of God, which is, while unknowable and unreachable, somehow present among us. The theme is articulated most acutely in “No Transcendence,” which begins, “Immanence proves an altogether far / more fitting goal.” For Cairns, the mission of every slow pilgrim is not to rise above the world into some ethereal realm of the holy, but to learn to see the holy in and around us.

Many of these poems dwell in the divine mystery of God, which is, while unknowable and unreachable, somehow present among us.

Right in the center of this collection, physically and thematically, is “My Comedy: Slow Pilgrim,” Cairns’s retelling of The Divine Comedy with himself cast into the role of Dante. What follows is a spiritual journey in which the speaker finds God with him at every point. In hell, he reports, “No one stands alone. Truth / stands ever here among us; Truth / Himself remains just here, attentive / and immovable within my υους [nous] .” And in purgatory, he observes that “one cannot quite turn away, not / any longer. He proves manifestly / present, everywhere.” In heaven, he finds that he has not actually arrived anywhere new; paradise “turns out to be precisely / where I have always stood, or sat, or languished unawares.”

As implied by the title, this collection returns again and again to the image of a lacuna, a word that refers to a gap or a missing part. Presumably, the lacuna in question is that chasm between God and man, and Cairns invites us not to transcend it, but to enter into it and welcome immanence. The opening poem, “Recuperating Lacunae,” sets the tone in its first lines: “No, not so much an emptiness, never yet / an emptiness.” After denying that this lacuna denotes in any way an absence, he instead compares it to the spiritual depth of a communion chalice: “…very like the cup held now / before you, abysmally full, a pool / roiling with boundless abundance, this cup / exceeding ken beyond measure.”

In “The End of Suffering,” Cairns takes this lacuna and places it inside of us, explaining that in a place of suffering:

…you might descend

into your long-abandoned core,where, mid uncommon darkness, you

may find the door, whose openingavails at last that lacuna

wherein the υους proves yet to bealso more spacious than heaven,

bearing also the Very God,who is most pleased to meet you there.

Poetry itself is something that comes up a lot in these poems, either as a topic of exploration or as an area of instruction in the aforementioned epistles. The speakers of these poems tend to highlight poetry as a necessary tool of spiritual development specifically because it invites the reader to slow down and examine the little pockets of non-emptiness where God and man can meet. This is made explicit in the opening stanza of Lacunae:

Say the gift of difficult syntax consists

in the many, fleeting, lit lacunae

glimpsed along the way, obliging the reader’s

own intermittent, meandrous detour

along the steep and cobbled path to the dense

sentence’s provisional—which is to say,

patently inconclusive—conclusion.

This passage is very close to Cairns’s argument for his own poetic style: a winding walk amidst heavy ideas, with lots of parenthetical clauses and the occasional lingering. Yet there are poems, specifically in the book’s third section, where Cairns seems to abandon this lofty style of verse in favor of the simple pleasures of life: fresh butter, a meal, the glory of nature. In “A School of Embodied Poetics,” the poem’s musings end with such an interruption: “My wife happened in the room, just / as I was imagining another / airy stanza. Enough, I thought, enough.”

The speakers of these poems tend to highlight poetry as a necessary tool of spiritual development specifically because it invites the reader to slow down and examine the little pockets of non-emptiness where God and man can meet.

In the grand narrative of this collection, this embrace of simplicity represents the truest understanding of immanence: that even the smallest things are lacunae beckoning us to enter, that we find the holy when we stop seeking it and look around. In one of the concluding poems, “Implicative Lacunae,” we get the image of something close to what Cairns might imagine as the conclusion of a slow pilgrimage: “…and he became a man without doctrine, / became a man intent on praise, / a man whose freedom would ever / expand, would ever reach towards.” No, Cairns reminds us, there is never yet an emptiness in this world; everything is full to the brim.

Matthew J. Andrews is a private investigator and writer. He is the author of the chapbook I Close My Eyes and I Almost Remember and the forthcoming full-length collection, The Hours (Solum Press). He can be contacted at www.matthewjandrews.com.